In this eight-week alert series, we are providing a broad look at current and emerging issues facing the energy sector. Attorneys from across the firm will discuss issues ranging from environmental disclosures and risk management in business transactions to insolvency, compliance programs and intellectual property. Please click here to read all of our recent publications.

This piece was also published by IP Law360 and Energy Law360 on March 9, 2016.

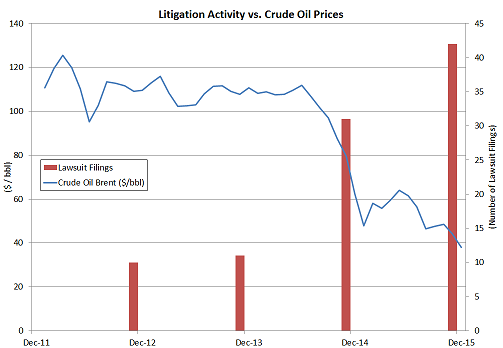

The recent slump in oil prices has impacted oil and gas companies in a variety of ways, some to be expected, some less so. One unwelcome development is that while these companies have been implementing cost-savings and other measures to offset decreasing revenues, their expenditures on patent infringement litigation have been increasing. The correlation between decreasing crude oil prices and increasing patent litigation within the oil and gas industry, whether incidental or consequential, has been noteworthy: during the same time period crude oil prices have experienced a more than threefold drop, patent litigation within the oil and gas sector has increased by more-than-threefold.1

While the majority of these cases reflect litigation campaigns launched by non-practicing entities (NPE), there has likewise been an increased volume of competitor cases within the oil and gas sector, possibly as companies attempt to offset declining sales revenues with licensing revenues. To confront the challenge of increased patent litigation during this time, companies facing patent litigation should consider several potential strategies.

Use of Inter Partes Review in Patent Litigation Strategy

As part of its overall defense strategy, a defendant accused of patent infringement can initiate a separate inter partes review (IPR) to challenge the validity of the patent(s). The procedure for conducting an IPR took effect on September 16, 2012, as part of the implementation of the Leahy-Smith America Invents Act (AIA), which expanded the then-existing inter partes reexamination proceeding. An IPR may be sought against any patent, regardless of issue date.

An IPR is a trial conducted by the Patent Trial and Appeal Board (the Board) in which the Board reviews whether the claims of a patent are patentable. Only patents and printed publications may be relied upon to show that one or more claims of the patent should not have been issued, and the claims may only be challenged as lacking novelty (an earlier reference discloses the invention) or on the basis that the claims are obvious (one or more references can be combined or modified in an obvious way to arrive at the invention.

An IPR proceeding begins when a third party files a petition for review of one or more claims of an issued patent. For example, a defendant accused of infringing certain claims of a patent can petition to have the asserted claims reviewed in an IPR. However, a defendant in this situation has only one year from the date of service of the complaint in which to file the petition. The patent owner has three months from the filing date of the petition to submit a preliminary response arguing why the Board should not review the claims. Three months from this preliminary response filing date, the Board will issue a decision on whether it will institute a review of any of the challenged claims. If the Board decides to institute a review, it will then issue a final written decision on the patentability of those claims within one year of institution of the IPR.

Aside from ending due to a final written decision by the Board finding for or against patentability of the claims, an IPR can be dismissed for procedural reasons, patent owners can disclaim (give up) claims, and/or the parties can settle and agree to terminate the proceedings. Thus, the outcome of an IPR is often more nuanced than merely a straight win or loss by the patent owner. However, generally speaking, IPR proceedings have been an effective tool for patent defendants. Based on all IPR petitions completed as of January 31, 2016, in about 64% of those IPRs, all of the instituted claims were found unpatentable, at least some of the claims were found unpatentable, or the parties agreed to settle.2 During the same period, IPRs resulted in complete wins for the patent owner in about 36% of cases.

Despite the more-than-threefold increase in patent litigation in the oil and gas sector from 2013-2015, data associated with IPR proceedings in this sector shows that the number of IPR petitions filed has remained relatively flat at less than 2% of all IPR petitions filed. Moreover, although lawsuits naming top oil and gas production companies3 also saw a threefold increase during the same time, none of the named companies appeared as a petitioner for an IPR on the patents asserted in the lawsuits.

This is despite the fact that for about 77% of those proceedings relevant to the oil and gas sector overall, all of the instituted claims were found unpatentable, at least some of the claims were found unpatentable, or the parties agreed to settle.4 Thus, it appears that IPR proceedings in the oil and gas sector have been an effective, but underused, tool available to defendants in the oil and gas sector.

Patent Clearance/Freedom to Operate

Given the effectiveness of the post-grant proceedings mentioned above, one can grasp the importance of carefully considering the use of these proceedings when faced with an accusation of infringement. However, patent litigation can be expensive, with the all-inclusive cost of defending a claim of patent infringement averaging $2.2 million in 2015 for cases with $1 million-$10 million at risk.5

How can energy companies avoid such litigation, or minimize their exposure when faced with such patent assertions? Some companies seek to better understand their risk by conducting patent clearance searching, which is also commonly referred to as performing a patent freedom-to-operate analysis. In the energy context, project planners, whether in the company's legal department or R&D department, often commence this type of legal project when the company is about to make a new investment or expansion. For example, when the company launches a new product or service, expands into a new market or industry, or plans construction on a new capital investment, the company seeks to understand whether its investment will further open it up to claims of patent infringement.

For example, a company considers purchasing equipment or technology for a big new project (e.g., drilling rigs, solar panels or wind turbines). The company is deciding between two vendors: Vendor A and Vendor B. Vendor B undercuts Vendor A on price by 20%, but the company's patent diligence reveals that Vendor A holds key patents on this technology and has actively enforced its patents in the industry. Because the costs for defending patent claims from Vendor A will likely dwarf the 20% price difference, and because Vendor B's pockets are not deep enough to indemnify the company, the company ultimately selects Vendor A at the higher price. Or, a similar set of facts could lead to a different outcome: upon “kicking the tires” on Vendor A's patents, the company decides that the patents are nowhere near worth the 20% premium and selects Vendor B, and fortifies itself against the eventual claim from Vendor A.

Will knowing about these patent risks discourage new investment? Not necessarily. Every new product or service offering carries with it some level of risk. Understanding the patent risk component, especially early in the process, permits energy companies to (1) modify their plans to reduce the patent risk, (2) obtain opinions of counsel to minimize the risk that any patent infringement verdict would be tripled due to alleged willful infringement, and (3) contractually shift the risk to other parties involved in the project. At the very least, understanding the patent landscape when diving in to a new project can minimize surprises, such as a “blindside” patent infringement claim, as well as questions from the company's leadership such as “why didn't we see this coming?”

Defensive Portfolio Strategy

Often, small- or medium-sized companies that find themselves defending a claim of patent infringement wish they had patents of their own with which to “fire back.” However, because the patent process usually takes several years, from application filing to patent grant, building a defensive patent portfolio necessitates a longer-term and deliberate strategy long before facing a lawsuit. A defensive patent portfolio strategy offers several advantages. First, it places arrows into the company's quiver should competitors try to copy its technology. Second, it gives the company ammunition to fire back if a competitor accuses it of infringement. Third, a defensive patent portfolio can create a deterrent effect to make the company a less attractive target for such claims. Fourth, a robust patent portfolio often makes a company a more attractive target for merger or acquisition. Fifth, as mentioned in the example above, patent coverage can convey leverage in a competitive bidding or vendor selection process. Finally, building a patent portfolio can make it more difficult for competitors to patent the same improvements themselves.

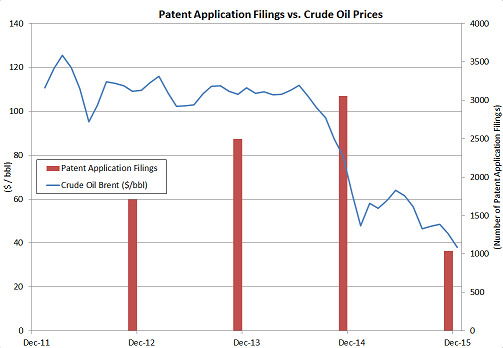

While building a defensive patent portfolio necessitates a longer-term strategy, the graph below illustrates a general correlation between the number of patent applications filed in the energy industry and the price of crude oil.6 While this could signal that more inventions are made when business is good, it could also signal that energy companies consider patent applications to be an optional asset to be developed as profits permit, rather than a core part of their competitive strategy. This can leave companies more vulnerable compared to competitors who continue to protect new innovations even during the downturns.

While a defensive patent portfolio strategy works for some companies, it also has limitations. For example, a defensive patent portfolio does not usually deter patent infringement claims from NPEs; as their moniker suggests, NPEs do not have any business of their own, and thus no products or services that could subject them to infringement claims. As another example, some companies simply do not innovate. If a company buys drilling equipment and performs well drilling services according to specifications, the company becomes invested in a current solution rather than searching for the next solution. However, sometimes a patentable idea comes out of those routinely using existing technology, and can be as simple as an employee asking “have we ever thought about modifying the rig by ____ to do ____?” In this way, even smaller companies can develop patent assets.

Patents as Revenue Generation

Large energy companies have been amassing defensive patent portfolios for a long time; they view it as a necessary strategy to remain competitive, build it into their yearly budgets, and foster a culture that encourages engineers and scientists within the company to recognize and submit new inventions for protection. Whether in a large company with a long history of regular patent filings or in a smaller company that is newer to the practice, sometimes company leadership asks about other revenue generation. Particularly as oil prices decline, energy companies look at their assets, including their intellectual property assets, and wonder whether any of them could generate revenue. This contributes to the trend reflected in the graph above: competitor sues competitor to recoup its R&D cost for new technologies, or smaller companies sell themselves or their patent assets to NPEs who then aim those patents at the entire industry.

In addition to deriving the defensive benefits of a patent portfolio, how can energy companies make money from their patent holdings? Companies can license their patents, but approaching other companies and convincing them to license technology can itself be risky. Often, the only way to convince a company that they need a license is to threaten a patent infringement action. This can backfire by inflaming tensions between the two companies, or by making the first company look like a patent bully in the marketplace. Even successful patent license negotiations require some level of policing or auditing to ensure compliance.

Government regulatory activity can also create opportunity for windfalls for patent holders. For example, if the government were to mandate that all well bore caps comply with new criteria, and if a company held patents on the only currently known well bore cap technology to achieve that criteria, those patents would become immensely valuable until a non-infringing alternative is discovered. Identifying these types of opportunities involves not only maintaining a steady defensive patent portfolio strategy, but also actively comparing the patent portfolio to competitors' activities, as well as staying abreast of regulatory developments. More than a handful of government agencies actively regulate the energy industry.7

With Every Downturn Comes an Upturn

As the price of crude oil remains low, energy companies may turn to their other assets, particularly their intangible assets like patents, to derive additional value. Adoption of a sophisticated intellectual property strategy will help energy companies weather the storm and position them for longer-term success. This includes defensive strategies like planning for potential litigation and understanding the array of available patent invalidation tools, building a defensive patent portfolio, and conducting patent freedom-to-operate analysis when launching a new product, service or capital project. Companies further maximize patent value by identifying licensing opportunities and positioning themselves well for purchasing or selling patent assets. Understanding the intellectual property risk profile associated with all of these activities will give energy companies an extra strategic edge when the price of oil rises again.

1 Crude oil pricing from the U.S. Energy Information Administration; patent litigation statistics from Oil and Gas Field Services and Natural Gas Liquids Industry Report, Thomson Reuters Monitor Suite, 2016.

2 See Patent Trial and Appeal Board Statistics 1/31/2016.

3 Based on Fortune Global 500 ranking by 2015 Revenue.

4 IPR filings and disposition information is based on the authors' review of data available in the Legal Analytics® Platform provided by Lex Machina™, a LexisNexis® Company.

5 AIPLA Report of the Economic Survey 2015, at I-106 (Litigation-Patent Infringement, All Varieties $1-$10M at Risk, Inclusive, all costs (000s) by Location (Q35Ae)).

6 Crude oil pricing from the U.S. Energy Information Administration; patent application filing statistics from Oil and Gas Field Services and Natural Gas Liquids Industry Report, Thomson Reuters Monitor Suite, 2016

7 For example: the Department of Energy, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, the Nuclear Regulatory Commission, the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management, Regulation and Enforcement, the Chemical Safety and Hazard Investigation Board, the Environmental Protection Agency, the Mine Safety and Health Administration, the National Institute of Standards and Technology, and the Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement. Lyons Sunshine, Wendy, Who Regulates Energy in the U.S.?, About Money (last updated Feb. 24, 2016).